Renewed Perspective on Platform Businesses

Introduction

Our previous note on platforms was published nearly four years ago. In that piece, we explored several foundational ideas, and our expectation that India would see a wave of platform IPOs over time.

Since then, the landscape has evolved meaningfully. Multiple platform companies have listed in recent years in India, while several are reaching an inflection point. In light of these developments, we believe it is timely to revisit and deepen our earlier framework.

The Power of Platforms

1. Dominance of Platforms at the Top of Global Market Capitalisation

Eight of the world’s largest companies by market capitalisation today are either platform businesses or critical enablers of platforms through semiconductors. Excluding Nvidia, TSMC, and Broadcom—primarily chip companies—the remaining five (highlighted in green below) are global platform leaders. Even the chip companies are deeply intertwined with the platform ecosystem as platforms are fundamentally driven by data, computing power, and scale.

| Top 8 Companies in the World by Market Capitalization | |||

| Company | Market Cap (USD Tn) | Company | Market Cap (USD Tn) |

| NVIDIA | 4.5 | Amazon | 2.6 |

| Alphabet (Google) | 3.9 | TSMC | 1.7 |

| Apple | 3.8 | Meta Platforms | 1.6 |

| Microsoft | 3.6 | Broadcom | 1.6 |

5 of the world’s largest platforms are:

- Google (Alphabet): Search, Maps, YouTube, Android, and Cloud

- Amazon: E-commerce and AWS

- Meta: Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp

- Apple: iOS and App Store ecosystem

- Microsoft: Windows, Office, Azure, OpenAI, and Dynamics

Despite their already massive scale, some of these companies continue to grow revenues at 15%+ year-on-year on a base of USD 200–300 billion. More importantly, their share of aggregate profits within the S&P 500 has been rising consistently over the last seven years, underscoring the disproportionate economic power of platforms.

2. Emergence of Listed Platform Companies in India

Platform companies warrant renewed discussion not only because they dominate global market capitalisation, but also because they are becoming increasingly prominent in India. Over the last few years, several platform businesses have listed, with more IPOs possible. Platforms are no longer a future promise in India—they are now publicly traded, investable businesses.

Indian platforms are embedded in our daily life spanning food delivery, grocery, building materials, cosmetics, apparel, insurance, lending, trading, air travel, hotels, education, jobs, automobiles, power, household services, gaming, and music. In many ways, this represents India’s technology showcase—consumer-facing, scalable, and formalised through public markets.

Despite this breadth, penetration remains low. Most Indian platforms currently serve only 2–4 crore users out of 140 crore people in India, highlighting the significant headroom for growth. For context, Meta’s platforms collectively serve nearly half of the world’s population. India’s most valuable listed platform company, Eternal, with a market cap of approximately USD 30 billion, operates two major platforms—Zomato and Blinkit. Even these platforms serve ~2% of India’s population today. This gap between current penetration and potential scale underscores why platform businesses in India remain early in their lifecycle, despite growing prominence.

3. Rapid Value Creation by Platform Companies

Platform companies have created enormous value in a relatively short period of time. Unlike traditional businesses, they have scaled without owning the physical assets typically required to build such large enterprises. Airbnb owns no hotels, and Uber owns no cars—yet both have substantial market cap versus the leader in their respective categories and within a short period of time. The same dynamic is now visible in India. Blinkit (acquired just 4 years ago by Zomato) is expected to surpass DMart’s (founded in 2002) revenues this year, despite not owning a single consumer-facing store.

Recap: What are Platform Companies and Their Key Stages?

Traditional businesses are linear in nature where competitive advantage is driven by process efficiency, cost control, or distribution strength. Scale is constrained by capital intensity and limited economies of scale. Platform businesses represent a fundamental shift in how scale and value are created. Instead of owning assets, platforms leverage technology, data, and network effects to substitute for physical infrastructure. This asset-light, technology-led model allows platforms to expand rapidly, reallocate capital efficiently, and respond dynamically to demand—enabling faster growth and disproportionate value creation compared to traditional linear businesses.

There is no predefined supply chain as multiple sellers and purchasers interact directly with each other which helps reduce friction and transaction costs and provides convenience and personalisation, with trust. Platforms have risen to prominence recently due to the maturation of the broader technology ecosystem—widespread smartphone adoption, mobile application developers, faster connectivity (including 5G), and availability of scalable cloud computing and AI.

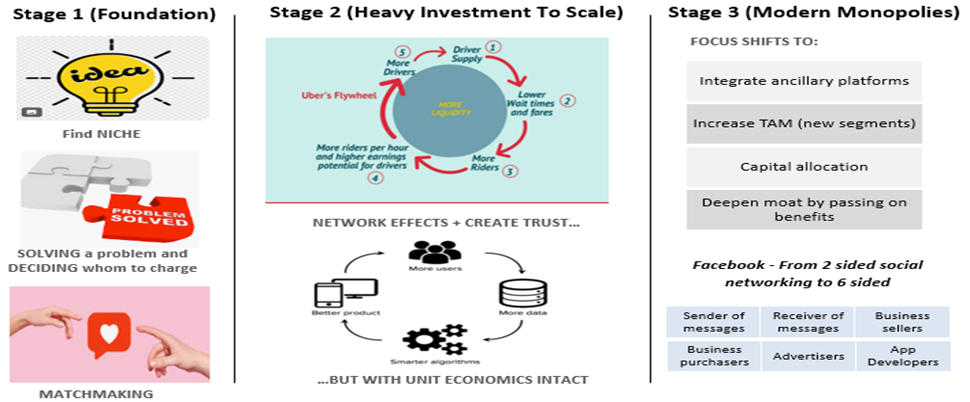

Key stages of the platform business

Stage 1: Build and Seed – The first stage involves identifying a niche where a real problem exists and where supply and demand can be matched efficiently. The focus is on seeding both sides of the platform while closely tracking early unit economics. Critical decisions are made around platform economics—who to charge, how to charge, and whom to subsidise to kick-start activity.

Stage 2: Scale and Monetise (critical) – Create network effects at scale by expanding its user base and increasing transaction frequency. Growth must be driven by product pull and quality engagement rather than excessive discounting; unit economics need to remain intact even as scale increases. Establishing trust, rules, and standards becomes essential. As the number of participants grows, effective matchmaking becomes increasingly complex, requiring more sophisticated algorithms.

Stage 3: Expand and Modern Monopoly – Once a platform reaches maturity and scale, incremental investment requirements decline significantly. Even if the platform was not the first mover, achieving scale can eliminate competition and result in long periods of dominance—creating what can be described as a modern monopoly. At this stage, platforms gain pricing power, leading to higher profitability, or they can reinvest surplus profits to deepen their moat and deter new entrants. Growth increasingly comes from capital allocation—adjacent platforms, new verticals, or expanding TAM.

Platform Profit & Loss Basics

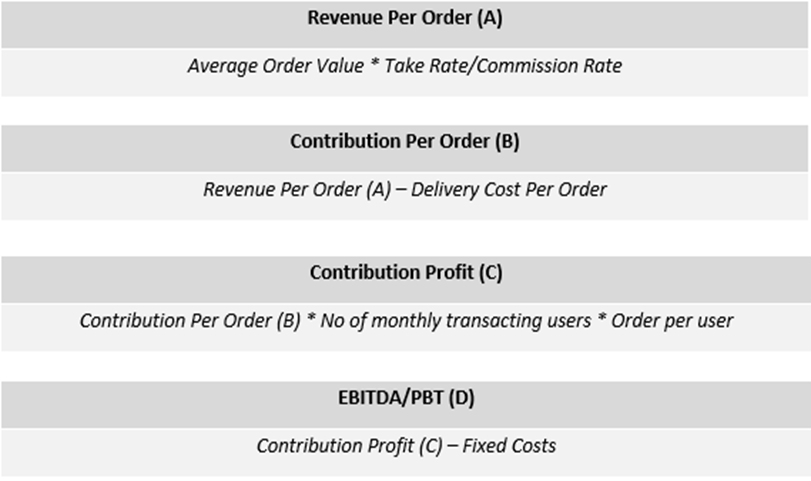

Having covered the theoretical framework, it is important to familiarize ourselves with the specific terminology and mechanics unique to platform businesses, and to understand the flow of a basic P&L statement for a platform—since it differs from that of traditional businesses.

This stepwise approach helps investors and analysts understand how user engagement, order economics, and cost structures combine to drive platform profitability, providing a clear picture of underlying financial health beyond headline revenue numbers. The framework will become clearer with an eg. provided later in this note.

Two Biggest Differences Between Platform Companies and Linear Businesses

1. Strong Balance Sheet

Platform businesses typically have very few fixed assets, little to no debt, and often operate with negative working capital. This results in a unique financial profile where:

- EBITDA = PBT = Operating Cash Flow = Free Cash Flow – Because platforms don’t own physical assets (think AirBnb or Uber), they avoid depreciation expenses, and with minimal debt, there’s little to no interest expense. Moreover, their cash conversion cycle is often negative—getting paid by customers before paying suppliers—leading to strong cash generation and a cash-rich balance sheet funded by early-stage private equity funding and operational cash flows.

- Extremely High Incremental Return on Capital Employed (ROCE) – While platform companies might show negative ROCE in their initial years due to upfront investments and lack of profits, this changes dramatically once the initial build phase is over. Since they require little to no incremental capital to scale further—no asset creation or large capital expenditures—their incremental ROCE approaches infinity. This means they can grow EBITDA and free cash flow substantially without needing additional capital, highlighting their exceptional capital efficiency compared to traditional linear businesses.

2. Non-linearity of P/L statement

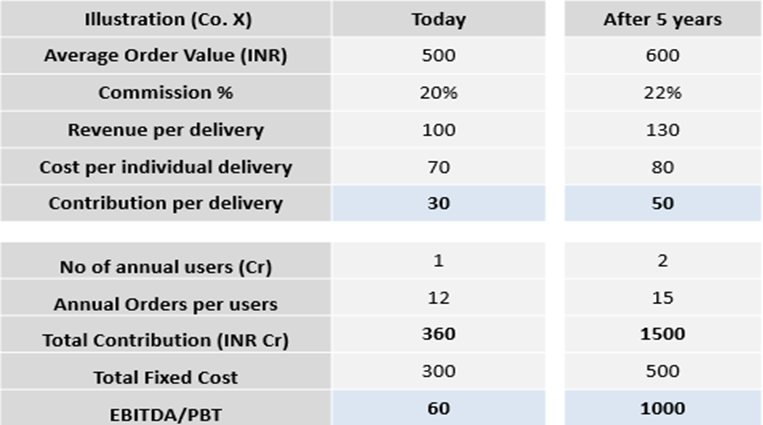

Unlike traditional businesses, the performance of platform companies is inherently non-linear. Subtle changes can make a massive difference. The example below helps illustrates this more clearly. The first column represents the platform in its early stage, when it is generating minimal profits. The platform has spent heavily to build itself but hasn’t yet achieved large scale. It is making ₹60 Cr EBITDA/PBT currently, with a market cap of ₹25,000 Cr. At first glance, it looks expensive on a P/E (Price to Earnings) basis. Five years later, the financials look very different.

While the number of users may increase just 2x due to low penetration, small improvements across multiple line items—such as average order value, commission rates, orders per user, and variable costs—compound and multiply, driving a 5x increase in contribution profits, far beyond what user growth alone would suggest. Fixed costs barely rise, as most investments in technology, employees, and infrastructure have already been made; incremental spending is typically limited to areas such as marketing or R&D. As a result, EBITDA/PBT scales multi-fold to ₹1,000 Cr, making a ₹25,000 Cr market capitalisation appear reasonable, or even inexpensive. Importantly, all of this is achieved without deploying significant incremental capital, adding physical assets, or tying up working capital—highlighting the unique economic power of platform businesses.

This illustrates the beauty of platform companies—the non-linear amplification in the P&L from relatively small changes in metrics, which is never seen in traditional businesses.

In addition, platform companies have multiple levers to mitigate cost pressures or enhance profitability, especially once they reach a position of dominance.

- Platform fees: Even a modest platform fee can materially impact earnings. For instance, an INR 5 per-order platform fee across 2 crore users with 15 orders per user annually translates into nearly INR 150 Cr of incremental EBITDA/PBT, with no associated costs.

- Advertising revenues: Platforms can also monetise their user base by charging brands for advertising and preferred placement. As user scale and engagement increase, advertising rates rise. Importantly, advertising income is almost pure margin, with negligible incremental cost, and flows directly to the bottom line. In this example, if the platform generates INR 100 Cr in incremental advertising revenue, EBITDA and PBT increase by the same amount immediately.

Key Tenets of Investing in a Platform Business

Scale is a non-negotiable pre-requisite—critical mass of network effects key for long-term relevance.

Winner-Takes-All Market Structure – Invest only in platforms operating in winner-takes-all or near winner-takes-all markets. A clear monopoly (≈70%+ market share) or a stable duopoly is critical, as network effects tend to concentrate value in the hands of very few players.

Timing: Buy When Cash Flow Predictability Improves – The optimal entry point is when profitability and cash flow visibility begin to improve at scale. Platform cash flows are inherently back-ended, and the risk-reward inflects materially once a credible path to steady-state economics becomes visible.

Account for Non-Linearity in Profits and ROCE – Platform businesses exhibit highly non-linear profit and cash flow trajectories. Small improvements in scale or monetisation can lead to disproportionate increases in EBITDA and incremental ROCE, which traditional linear models fail to capture.

Focus on Underlying Operating Metrics – Do not anchor on quarterly reported earnings. Instead, track the underlying operating metrics—such as user growth, engagement, take rates, cohort behaviour, and unit economics—which are far more indicative of long-term value creation.

Continuously Monitor Key Risks – Key risks include poor capital allocation, technological disruption, intensifying competition, and adverse regulatory changes. Mortality risk is key risk for platforms and hence these factors need to be actively monitored to ensure network effects are not getting eroded.

How to value them?

Platform businesses typically list at high P/E multiples as they are early-stage and profitability has not yet materialised. Traditional valuation tools such as near-term P/E or DCFs are often unreliable. P/E may not be the right metric when earnings are depressed or negative. DCF (Discounted Cashflows) requires 25–30 years of cash flow projections and terminal growth assumptions, which are highly uncertain for tech-driven platforms with elevated mortality risk. As a result, valuation must focus on when the platform reaches steady state, rather than attempting to precisely value distant cash flows.

Step 1 – Adopt a 5-year forecast horizon as we are investing in those platforms only which have a visibility to reach mature margins or stable unit economics within this period. It is difficult for competitors to displace a scaled platform with strong network effects in a short time frame. This horizon balances realism in forecasting with sufficient time for operating leverage to emerge.

Step 2 – Build two operating scenarios—Base and Bear—and assign probabilities to each, recognising the high variance in financial outcomes typical of platform businesses (as illustrated above). Management guidance on steady-state EBITDA margins (as a percentage of GOV/NOV) can serve as an anchor for these scenarios. Probability-weighting the outcomes converts uncertainty into a more robust estimate, rather than relying on a single-point forecast.

Step 3 – Determine an appropriate valuation multiple based on growth beyond Year 5. ~15% growth can trade at 30–35x P/E while ~20–25% growth can trade up to 50x P/E as well. Multiples should be benchmarked against high-quality B2C businesses with strong ROE, durable moats, similar growth. Apply the selected multiple to Year-5 earnings to estimate the market capitalisation at that point, and evaluate whether the implied CAGR over the five-year period meets the investor’s required return.

Conclusion

Despite India’s vast population, most platform companies today serve only about 2–5% of the population. For example, Zomato and Swiggy’s food delivery GMV (Gross Merchandise Value) is under USD 5 billion annually, significantly smaller compared to global peers like Meituan (China) and DoorDash (USA), both exceeding USD 100 billion in GMV.

Many Indian platforms remain in a heavy investment and growth phase but are now approaching profitability inflection points. Their scale and unit economics are beginning to mature, setting the stage for strong future profits and cash flows.

Example: Blinkit (Quick Commerce) – If Blinkit achieves management’s guided EBITDA margin of 5% of Net Order Value (NOV), profits could approach INR 8,000 crore in ~5 years, assuming continued rapid dark store expansion. Zomato (Food Delivery) could generate INR 5,000 crore in EBITDA in 5 years. Together, this could imply roughly INR 13,000 crore (~USD 1.7 billion) for Eternal as a company in EBITDA/PBT/cash flow after ~5 years, assuming margin targets are met.

Many platforms could become highly profitable while still growing at 15–20% annually, benefiting from operating leverage, network effects, and expanding Total Addressable Market (TAM). Predicting exact financial trajectories remains difficult due to the non-linearity of platform economics and high mortality risk. Valuing platforms is challenging given evolving business models, competition, and technology disruptions. Despite this, platforms represent unique opportunities to capture disproportionate growth driven by technology, with benefits for multiple stakeholders (consumers, merchants, delivery partners, investors).

Indian platforms are still emerging but hold enormous potential. While caution and rigorous financial modelling are necessary, ignoring the transformative power of platforms is unwise — they are reshaping industries and creating new market leaders.

Warm Regards,

Kshitij Kaji,

Vice President – Research

Fund Manager – SLMP

SageOne Investment Managers LLP

Legal Information and Disclosures

This note expresses the views of the author as of the date indicated and such views are subject to changes without notice. SageOne has no duty or obligation to update the information contained herein. Further, SageOne makes no representation, and it should not be assumed, that past performance is an indication of future results.

This note is for educational purposes only and should not be used for any other purpose. The information contained herein does not constitute and should not be construed as an offering of advisory services or financial products. Certain information contained herein concerning economic/corporate trends and performance is based on or derived from independent third-party sources. SageOne believes that the sources from which such information has been obtained are reliable; however, it cannot guarantee the accuracy of such information or the assumptions on which such information is based.